This article analyzes common politeness errors made by learners of French whose native languages are Uzbek or Russian. Through a linguo-pragmatic and linguo-cultural approach, the study explores how cultural and communicative norms in the native language interfere with the acquisition of appropriate politeness strategies in French. Using Brown and Levinson’s (1987) face theory as a framework, the paper categorizes frequent errors based on learner corpora and suggests methods for minimizing interference. The findings are significant for language pedagogy, translation studies, and the development of intercultural communicative competence.

Keywords: politeness, interference, linguistic pragmatics, linguocultural studies, face theory, French language, native language, speech errors, foreign language learning.

Встатье рассматриваются типичные ошибки вежливости, возникающие у изучающих французский язык с родными узбекским и русским языками. Анализ осуществляется с позиций лингвопрагматики и лингвокультурологии. Исследование опирается на теорию «лица» Брауна и Левинсона (1987) и показывает, как культурные различия между родным и изучаемым языком влияют на усвоение стратегий вежливости. На основе анализа корпусов классифицируются основные ошибки, предлагаются пути их минимизации. Работа актуальна для методики преподавания иностранных языков, теории перевода и межкультурной коммуникации.

Ключевые слова: вежливость, интерференция, лингвопрагматика, лингвокультурология, теория лица, французский язык, родной язык, ошибки речи, изучение иностранного языка.

Politeness plays a crucial pragmatic role in social communication. Every culture has specific ways of expressing politeness, and the misinterpretation of these cultural nuances by language learners often leads to pragmatic speech errors. According to Brown and Levinson’s (1987) Face-Saving Theory , every individual possesses a concept of «face,» which they strive to maintain or support through various communication strategies.

In French, politeness is expressed through social hierarchy, language registers, and grammatical structures (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 1996). However, learners of French, particularly native speakers of Uzbek and Russian, tend to rely on politeness norms from their mother tongue, leading to significant misapplications of French politeness strategies.

Native Language Interference: Concept and Impact

L1 interference refers to the transfer of phonetic, lexical, grammatical, or pragmatic features from the mother tongue to the target language (Odlin, 1989). In the realm of politeness, such interference is particularly evident in sociopragmatic misinterpretations. For instance, Uzbek learners frequently embed religious elements in requests—such as «May God be pleased» or «Be human» -which have no direct equivalents in French and may produce unintended connotations. Vezhbitskaya (2001) also notes that Russian politeness is grounded in cultural notions of sincerity and the «soul,» which may clash with the formal-informal dichotomy of French politeness.

Politeness Strategies in French

Politeness in French is grammatically encoded. For example, the conditionnel présent tense is used to soften imperatives: «Je voudrais savoir si vous êtes disponible.» Learners unaware of this grammatical strategy may opt for direct imperatives like «Vous venez ici!» , which may sound abrupt or even threatening (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 2005).

Béal (1992) emphasizes the importance of choosing the correct vous/tu register to reflect appropriate social distance. Misuse of the informal tu in inappropriate contexts is a common error among learners, leading to communication breakdowns.

Corpus Analysis of Politeness Errors

A learner corpus was compiled to analyze politeness-related errors in French among Uzbek and Russian-speaking students. The corpus consists of over 1000 written and spoken texts produced by 50 Uzbek and 50 Russian learners.

|

Type of Error |

Uzbek Learners (%) |

Russian Learners (%) |

|

Incorrect use of language register |

35 % |

30 % |

|

Lack of request formulas |

25 % |

20 % |

|

Use of direct imperative tone |

20 % |

25 % |

|

Patronymic interference (Russian only) |

0 % |

25 % |

These results reflect, for example, the Uzbek learners’ inconsistency in using «vous» and «tu,» the underuse or misplacement of politeness markers such as s'il vous plaît or je vous prie , and culturally inappropriate direct requests ( donne-moi le livre instead of pourrais-tu me passer le livre? ). Russian learners often transfer their cultural practice of including patronymics (e.g., «Monsieur Ivan Ivanovich»), which has no functional equivalent in French and can cause confusion (Vezhbitskaya, 2017).

These findings highlight the necessity for learners to acquire not only grammatical knowledge but also cultural competence. In Uzbek, politeness is often expressed via blessings or religious idioms (e.g., «May God grant you…» ), which are incongruent with the secular and structured French formal style (Brown & Levinson, 1987). As a result, learners may misuse politeness forms or avoid them entirely (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 2014).

Factors that contribute to interference include:

- Lack of awareness of intercultural differences;

- Insufficient development of linguo-pragmatic competence;

- Inability to distinguish between language registers;

- Overly formal or literal translation approaches.

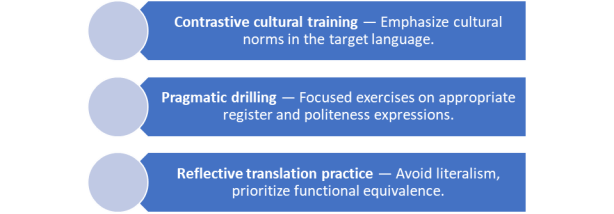

To reduce these instances of interference, a three-step pedagogical approach is proposed:

As Plantin (2011) asserts, politeness functions as a form of «social capital,» which cannot be internalized without contextual and cultural immersion. Therefore, teaching the structural and cultural dimensions of French politeness is essential for meaningful communication.

Politeness-related errors observed in the process of learning French as a foreign language among native Uzbek and Russian speakers should not be interpreted solely as grammatical inaccuracies or superficial linguistic mistakes. Rather, they are manifestations of a deeper, more complex phenomenon— intercultural and pragmatic interference . Such interference stems from the culturally specific politeness norms that are deeply rooted in the learners’ native linguistic and sociocultural systems.

The empirical findings of this research support the hypothesis that politeness is not a universally transferable construct. While formal grammatical structures such as conditionals or pronominal distinctions ( tu/vous ) can be taught explicitly, the sociocultural underpinnings of politeness—such as expectations regarding social hierarchy, religious influence, sincerity, and emotional expressivity—differ significantly across languages and cultures (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 1996). For instance, the Uzbek learners’ tendency to integrate culturally respectful expressions like «Xudo xohlasa» (God willing) or «inson bo‘ling» (be kind/human) into French communication reflects not merely a translation issue, but a mismatch in cultural pragmatics and communicative intent.

Furthermore, Russian learners often replicate sociolinguistic conventions such as the use of patronymics or literal translation of idiomatic expressions, which may convey unintended formality, irony, or even rudeness when directly transferred into French (Vezhbitskaya, 2001). These findings reaffirm that language learners do not acquire politeness strategies in isolation; rather, they filter them through their own native cognitive and communicative frameworks , which act as both a resource and a barrier.

To address these challenges, language pedagogy should incorporate explicit intercultural pragmatics instruction . This entails moving beyond syntactic accuracy and integrating authentic discourse analysis, socio-cultural comparisons, and reflective pragmalinguistic training. In particular, learners must be guided to recognize when and how politeness is grammatically encoded in French (e.g., through modal verbs, conditional constructions, and fixed expressions), and how such forms relate to invisible cultural scripts (Wierzbicka, 1999).

Moreover, the development of linguo-pragmatic competence —the ability to interpret, evaluate, and produce culturally and contextually appropriate speech acts—should be prioritized alongside traditional linguistic competence. Language educators must also foster metapragmatic awareness, enabling learners to question assumptions derived from their native linguistic worldview and to adopt new communicative strategies suitable for the target language.

In conclusion, this study reaffirms the need for a holistic, contrastive, and context-sensitive approach to foreign language instruction. It encourages the integration of intercultural training, corpus-informed pragmatics, and dynamic pedagogical interventions aimed at reducing pragmatic failure. Ultimately, fostering communicative competence in a foreign language demands that educators and learners alike recognize the profound entanglement of language, culture, and identity in everyday interaction.

References :

- Ayoun, D. (1999). Verb movement in French L2 acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 2(2), 103–125. DOI: 10.1017/S136672899900022X grafiati.com+1mdpi-res.com+1

- Buteau, M. F. (1970). Students’ errors and the learning of French as a second language. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 8, 133–145. Найдено через ERIC: EJ024623 moluch.ru+3eric.ed.gov+3tc.columbia.edu+3

- Fu, L., Fussell, S. R. & Danescu‑Niculescu‑Mizil, C. (2020, ноябрь 30). Facilitating the Communication of Politeness through Fine‑Grained Paraphrasing. arXiv. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.00012 arxiv.org+1arxiv.org+1

- Kumar, R. & Jha, G. N. (2021, декабрь 3). Translating Politeness Across Cultures: Case of Hindi and English. arXiv. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.01822 arxiv.org+2arxiv.org+2arxiv.org+2

- Danescu‑Niculescu‑Mizil, C., Sudhof, M., Jurafsky, D., Leskovec, J., & Potts, C. (2013, июнь 25). A Computational Approach to Politeness with Application to Social Factors. arXiv. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/1306.6078 arxiv.org+1arxiv.org+1

- Jarvis, S. & Pavlenko, A. (2008). Cross‑linguistic influence in language and cognition. London: Routledge. Термин «crosslinguistic influence» можно найти в обзоре transfer‑теорий en.wikipedia.org+1en.wikipedia.org+1

- Włosowicz, T. M. (2020). Teaching and learning French as a third or additional language in an international context: Selected aspects of language awareness and assessment. Neofilolog, 55(2), 239–263. DOI: 10.14746/N.2020.55.2.6 academia.edu+1researchgate.net+1

- Хайдарова Д. З., Идальго Р. М. Р. Сравнительно-типологическое исследование дипломатических терминов в испанском и узбекском языках //Журнал гуманитарных и естественных наук. — 2024. — №. 9. — С. 36–46. https://journals.tnmu.uz/index.php/gtfj/article/download/314/350