Keywords: water governance, institutional mechanisms, cooperation, transboundary river, management regime

Introduction

Transboundary water resources management has a great impact on the social and economic growth of the population of the states, diplomatic interstate relations, and the development of the region as a whole. In this regard, many developing and middle-advanced countries of the regions, in order to promote the economic growth of their countries to effectively use transboundary water resources and preserve the quality of the environment began to introduce different institutional governance mechanisms to support interconnection with each other. Consequently, the Central Asian (CA) region still needs stronger cooperation at the interstate and regional levels to manage water resources in transboundary rivers.

This paper aims to identify the theoretical concepts of water governance, the effectiveness of institutional architecture and their significance in actual situations, and their impact on transboundary water regimes and cooperation.

This study is considered by analyzing the theoretical concepts and existing practices operating within these theoretical concepts and current institutional mechanisms in the context of transboundary water management of foreign countries. At the heart of good transboundary water management is an institutional architecture that effectively coordinates sustainable economic development and conservation, promotes equitable use, and strengthens regional security (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

1. The significance of water governance

By the water governance, two meanings need to be distinguished, such as normative and analytical. Governance relates to a separate analytical procedure of regulation and coordination. It is an analytical method that is used to characterized and estimate actuality. The concept of governance is aimed at analyzing the development of reality, and responding to changes in reality that require new approaches in analysis. On this basis, regulation and control are conducted in an interconnected way between national government authorities at local levels, transnational organizations, civil society, and private stakeholders, and all these levels are included in the term «multilevel governance (Sehring, J. 2009).

The interpretation of water governance, expressed by the Global Water Partnership and later accepted and amended by the UN is (Sehring, J. 2009): “the governance of water in particular can be said to be made up of the range of political, social, economic and administrative systems that are in place, which directly or indirectly affect the use, development and management of water resources and the delivery of water services at different levels of society. Governance systems determine who gets what water, when and how and decide who has the right to water and related services and benefits” (Sehring, J. 2009. 62).

The water governance hangs not only on specific institutions as well on governance context. Water governance includes all political and socio-economic structures, as well as formal and informal laws and mechanisms that affect water use and allocation. Moreover, the government, civil society, and the private sector are all participating.

The current water issues in Central Asia are a consequence of the failed concept of sustainable water management. Managing Central Asia's transboundary waters need understandable and extensive rules that are adaptable enough to address present and upcoming issues for the regional water field (Barbara, J.P. 2014). Preserving basic legal standards for transboundary water management is a path to ensure the regional sustainability, progress, as well as relate beneficial inter-state collaboration across Central Asia and Afghanistan.

The management of transboundary watercourses, including Central Asia, requires fundamental principles reflected in interstate treaties on aquatic legislation as well as in customary aquatic legislation. In Central Asia, the procedures and principles on equitable and reasonable utilization of waters, the absence of significant harm, the principle of cooperation, and the general rules and law for the determination of the duties of States still need to be supplemented (Barbara, J.P. 2014). A prerequisite for the implementation of equitable, reasonable, and minimally harmful management of transboundary waters is the obligation of state cooperation under the UN-Water Convention. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, independent state water regimes and interstate cooperation in transboundary river management have been established in Central Asia and still need to be improved. States can combine the use of nomerous tools, especially on information exchange and consultations (Barbara, J.P. 2014). In States' obligations, regardless of the conclusion of the agreement, they intend to give notice of planned actions that are capable of causing significant transboundary harm. But such partnership frameworks are absent from the practice of transboundary water management agreements in Central Asia (Barbara, J.P. 2014).

A large number of organizations and institutions are used in the management of transboundary waters. By this method, these organizations are the result of negotiations and influential relationships, and they are shown in different characters and at different scales. They explain the diversity of views on the nature of the river and take practical forms at different scales.

2. The transboundary water management regimes

This section discusses the transboundary water management regime from a theoretical and empirical perspective. The term «regime» is used here to express the form of management. The regime encompasses specific normative frameworks, objectives, instruments and actors. In the experience, it can be implemented in different territorial ranges, which do not necessarily correspond to administrative and political limits. Consequently, the regime is a context of actions, not of the action itself. The analysis of regimes makes it possible to portray the different perceptions, priorities, and uses associated with the river (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger describe three types of management regimes: integrated, mono-functional polycentric. The integrated regime expresses a holistic management strategy, analyzing the river basin as an ideal unit for river management. The multifunctional regime considers transboundary water management through a multifaceted variety of activities involved in the process. The polycentric regime is characterized by the simultaneous functioning of multiple spheres of decision-making within a loosely coupled system. The three regimes listed above can be seen as a reference kind of social reality simplification or theoretical outline. They can coexist — overlap, complement each other, mutually enrich each other, or replace each other over time. Thus, authors considered a subsequent analysis of the transboundary governance of the Rhine River, which allowed them to clarify not only the historical background of the transboundary governance of the river but also the current problems.

2.1 The Integrated Management Regime

Since the application of the concept of «integrated water resources management» at the beginning of this century, the integrated regime has become a special focus of independent oversight bodies, scientists and trainees. The integrated trend is widely disseminated by many international organizations such as UNECE, UN-Water, GWP, as a standard approach. What is more, Goal 6 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development makes this approach the focus of its specific target1 on water resources. (C. Bréthaut, G. Pfieger. page 41)

Regarding transboundary water management, this approach uses river basin boundaries as the unit of reference, but not political or institutional boundaries. This regime is recognized as consisting of several entities and types of uses, united in an organization responsible for the joint management of river basin relations. According to the authors' analysis, the river becomes a “common property,” with stronger international coordination and even integration of public policy objectives aimed at defining a river basin-wide regulatory regime (C. Bréthaut, G. Pfieger, p. 41).

The states, at the framework of rules, move to a river basin organization to address certain issues regarding water resources and management of these resources, which further increase their activities and organization with the participation of stakeholders (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020). Such management regime has its positive characteristics. For instance, it allows reducing transaction costs, and will be able to strengthen the regulation within the river basin, as well as contributes to communication, reducing repetitive activities. The attitude towards integration is most felt in Europe for the management of large transboundary rivers, like the Rhine and Danube, and is carried out through international basin organizations, the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine, the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

The effectiveness of the integrated regime according to the regulatory proposals is very satisfactory, although according to the analysis of the authors, there are comments on this form of management (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020). For instance, the true degree of integration of national frameworks into an integrated regime’s institutional architecture can be questioned: there are substantial difficulties in integrating the objectives of different riparian public policies for managing transboundary waters, while the importance of overarching frameworks and of international law remains undeniable. What is more, the holistic perspective adopted by this type of regime does not necessarily translate into significant progress on the ground (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020. 41–42). According to other authors, exclusively organizing with limit bars gives significant consequences, and it is explained that river basin organizations face difficulties in the parallel integration of economic, social and hydrological issues in a single structure (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020). Ultimately, there needs to mention the financial resources for investment to organize the tracking of the basin organization, human resources, planning universal solutions, and data collection to determine the effectiveness of the structure (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

Once all these requirements are satisfied, however, an integrated regime is capable of succeeding in successfully structuring and organizing water resources management on a transboundary scale (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).The demonstration of the example of the Rhine River shows the ability of river basin organizations to effectively bring actors together around the challenges of a joint river, specifically to enhance the coordination among various actors (governments, economy branches, NGOs, environmental protection) and promote the processes of participation(C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

2.2 The Monofunctional Management Regime

An integrated perspective rarely meets the challenges of transboundary management. Regulatory challenges may arise in a particular section of the river, for a particular stakeholder group, or in an industry where the river water is used for a precise purpose, i.e., for production or services. Moreover, states are in a position to influence cross-border governance, clearly, other actors may also occupy key regulatory roles (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

Transboundary rivers are often managed by implementing a monofunctional regime. The principle of such a regime is to solve significant problems in the management of the river. Such a regime can be implemented by creating a commission to address a specific regulated issue (a purely administrative body) or by creating a management system around a limited number of leading sectors (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

The authors, on the basis of the results of their analyses, noted that such a system made it possible to guarantee the continuous possibility of producing goods and services by suitable sections. Moreover, it supported the regulation of important uses of the river and the constant coordination of competition. Consequently, the multifunctional mode helps to anticipate the probable conflicts in the use (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

Therefore, the nonfunctional model provides an alternative perspective on institutionalization and territoriality. It is designed frequently across political, administrative, and hydrological boundaries and is described by an institutional architecture built around the challenges and rivalries of use that have to be solved in order for the system to perform at its best. It is implemented through a particular configuration of participants and cooperation between sectors of activity (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020). This type of governance regime has been characterized in many studies as the way in which territorial governance can rely on different institutional structures. As noted in other works of literature on border-spanning regimes, the literature on territorial institutionalism and works on multilevel governance has added to this picture by offering various ways of thinking about the connection between the issue of group action and the ideal institutional arrangement for solving that issue (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger are focused on the term functional regulatory space, developed to complete certain lacunae in the analysis of regulatory frameworks of policy sectors, institutional territories, and governance areas. A functional is considered to be a space that applies ad hoc criteria (for this) to identify geographical and social areas deemed appropriate for the management of the issue that has to be solved (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).Different customizations are needed to reach the goals of the normative space. Of particular note is the redefinition of the relations between the different policy sectors involved, the creating of new geographical spheres designed to manage the challenge, and the re-defining of public policy obligations among the various layers of government. The functional area is organized around the management of competing uses and regulatory instruments for arbitration of disputes. It can cover political limits in an effort to ensure maximum optimization of the activities related to sectors, thereby decreasing tensions over the use of a joint river (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

The monofunctional perspective can be realized by institutions or organizations that strive to unify the ideas of one specific sector of interest and to coordinate it across borders (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020).

2.3 The Polycentric Management Regime

“Polycentrism is a concept that has long been used by researchers looking at urban development models and centralization/decentralization processes, in particular those with a critical perspective on change in metropolitan areas of the United States and Europe and on the imbalances that can arise between centre and periphery or between places of residence and places of work” (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020. P.45). In the second half of the ХХ century, organizations with a direction toward decentralization were exposed to the condemnation of regulatory and cost problems. C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger considered in their study the relationship between institutional activity and the clarity of theory. They found that polycentric management is more effective than a single-point decision-making organization. Moreover, this type of organization is able to function in an orderly manner in making accurate decisions on controversial and conflicting situations.

The polycentric regime refers to the integrated arena systems for establishing solutions in large-scale dynamics combining «bottom-up» and «top-down» processes (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020 ) . The polycentric regime refers to the integrated arena systems for establishing solutions in large-scale dynamics combining «bottom-up» and «top-down» processes. In the framework of this control system, on a self-organized basis, if the parties understand the difficulties in solving collective action, they seek arbitration at a higher level (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020). By this intention, such arenas are created to solve the exact problems appearing in the river basin.

There is some superiority of the polycentric regime. Its bottom-up dimension affords the application of local knowledge, both in explaining the collective-action problem that requires to be solved and inputting a decision-making process into effect. In doing so, it must strive to develop more inclusive, equitable institutional arrangements (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020). This network approach facilitates the attraction of actors involved in processes characterized by constant instability and the importance of constant adjustment. Moreover, the inherent institutional fragmentation of the polycentric regime contributes to its adaptability in the face of change and abiding sustainability (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020 ). To summarize, competition between different spheres should generate innovation in problem solving.

In practice, the authors (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger) cited the Rhine River as an example, illustrating the disadvantages of a polycentric regime in a nutshell. They pointed out the difficulties of regulating the presence of a large number of actors and institutions, and their operation within such a system of governance, with the possibility of duplication or overlap. The division and diversity of agreements between the stages of decision-making also make the management system more opaque, and this is all the more true in a transboundary context characterized by different institutional and regulatory frameworks (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger 2020). Consequently, opacity can also play an instrumental role, affecting attitudes of power, dominance, which create problems for joint cooperation on the management of the resource.

Thus, the authors (C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger) presented various theoretical models that were used in the development of examples of real-world scenarios and various approaches in the governance of various transboundary rivers.

3. Theoretical determinants of effective governance for transboundary water resources.

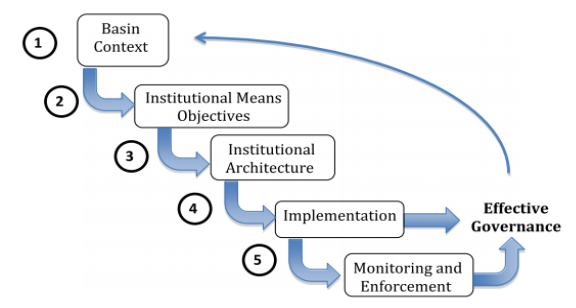

According to study of Glen S. Hearns, Taylor W. et al. 2014, designing an effective institution for transboundary water governance is viewed as a 5-step approach, which is shown in Figure 1 below. The first step is to analyze and understand the basin situation or context in order to design the appropriate institutional means to achieve the goals, the second step. In the third step, they will determine the architectural design of the institutional arrangement for the management regime. The design is followed by implementation, which is the fourth step, and finally, enforcement and monitoring. When all steps are carried out appropriately, an effective governance regime should involve regular revision of the basin situation and the institutional mechanisms designed. It is important since the physical environment and watershed or seawater resources can change, and socioeconomic assets and dynamics in a transboundary water scenario frequently shift over extended durations. This reflection framework should ideally be built into the architectural design phase (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Fig. 1. Basin context

Next, we will be considered on fundamental levels in more detail.

Basin context

Competition over the role of transboundary waters which are both drivers of regional development and essential objects of biodiversity protection, renders the challenges of appropriate management difficult. Transboundary water use is a potential source of tension among the basin nations competing over scarce supplies. Such waters may also present challenges of a diplomatic nature that often bind states in an asymmetrical relationship between headwaters and low-lying waters, or in a «common-use tragedy» kind of conduct with aquatic reserves (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

An institutional design is not blueprint. The frameworks must be adapted to the specific context of transboundary waters and represent its hydro-ecological, political-economic, socio-cultural conditions (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). The nature and features of resources determine institutional design (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

The effective basin institution establishing should start by defining and recognizing the interstate and need of the basin actors. Determining such needs and concerns involves both the problematic situation in cross-border water conditions and achieving cooperative arrangements, then assessing the present case in a specific watershed (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

There are few cases that would create institutions from the foundation, but in general there is no need, since a certain level of cooperation and framework already exists. But it may happen that current attitudes become non-functional or ineffective, and the necessity of creating new frameworks to reach institutional aims arises (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

No institution will be successful, at the end, unless the basic concerns of the actors are not taken into account. Comprehension of interests helps to identify a relative priority of institutional objectives, which determine the development of the architecture. Such a process is usually termed «interest-based negotiation», where the focus is on exploring objectives rather than positions (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Institutional means objectives

After understanding the context of the basin and ascertaining the interests of the various parties, the process of defining institutional goals begins. Institutional goals can be divided into the following categories:

1) Balancing incentives;

2) Reducing uncertainty;

3) Building trust and confidence;

4) Reducing costs/maximizing financial benefits.

Cost reduction is considered separately from incentive balance, as it may also involve the financial advantages, as this is a concrete goal to the institutional arrangement to be developed, as distinct from the causes of the institutional arrangement to be created in first place. Proper identification of fund goals can help provide for the installation of an adequate architecture (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Next, we will consider on each of these goals.

Balancing incentives

Establishing a «basket of benefits» helps parties to accept particular conditions of a common arrangement that might not seem reassuring in isolation in order to achieve an agreement (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). A major impetus for cooperation is the elimination or alleviation of a particular issue. There are many cross-border water agreements that aim to alleviate the issue. Challenge alleviation activities will impact every part of the institutional architecture, from determining an institution's scope to the information required for facilitating policy adoption, as well as rules and regulations (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Related to issue alleviation is equity, either in terms of distributing the benefits of irrigation water or hydropower or in terms of the costs of infrastructure and research(G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

To determine what constitutes a reasonable and equitable use, the participating states have to consider all relevant factors and circumstances, involving geographical and other environmental features, the socio-economic needs of the cooperating States, the populations dependent on water sources in each cooperating State, the impact of water sources in one cooperating State on other cooperating States, as well as «the comparative cost of alternative means of meeting economic and socio-economic» (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Reducing uncertainty

Uncertainty is often a major obstacle to successful agreements or decisions. That includes the bio-physical uncertainty associated with the resources, and the costs of enforcement, the conduct and obligations of other actors, as well as the needs and growth of development.

According to the G. S. Hearns and his colleagues (2014)analysis, “the failure to incorporate equitable rules governing water use into transboundary water treaties exacerbates the riskthat existing uncertainties will lead to undesirable outcomes such as increased water scarcity, resource degradation, and inequitable distribution.” (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

In scenarios where uncertainty exists about a resource caused by climate change or by other factors, it is important to ensure a strong level of information collection and sharing within the institutional architecture (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

A more crucial dimension of working with uncertainty is to develop an institutional framework which can handle changes due to both climate change and social factors. The key to effective change is having enough information to make adequate governance judgments about resources and their related users, as well as the flexibility and sustainability built into the institution (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Building trust and confidence

According to the author's analysis, one of the effective ways to achieve an agreement concerning the case of transboundary waters is to promote a positive attitude toward the basin's riparian countries. Treaties may be substantive — the ones concerning specific advantages, like flood management and energy creation; as well as more diplomatic or structural, that focus exclusively on fostering positive relations (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Strengthening trust is usually not an obvious factor in the design of Institutional frameworks, even though in many instances it is included in the resulting architectures. The trust may also be captured in significant parts about how resources will be distributed (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Confidence-building measures in the theory of diplomacy are mechanisms used to build trust and facilitate dialogue among the parties where confidence has to be built up before a more substantive deal can be reached (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). These may range from one-sided actions, such as a self-declared moratorium on resources production or a decrease in the rate of development, to the more interactive arrangements, for example information exchanges, «informal» dialogue meetings for testing policy options, and the launching of exploratory negotiations (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). A further feasible point to address trust strengthening is to create an institution that can develop to assume extra dimensions of transboundary water management as it evolves, and not try to be all things to all people from the beginning (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

The theory of negotiation supports progressive co-operation to strengthen the confidence of the parties (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

The resolution of disputes is commonly viewed as an important trust-building tool among the party’s (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). The systematic and effective dispute resolution mechanisms in transboundary water treaties fulfill their crucial role (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Beyond dispute resolution, increased attention to building trust can be reflected in the institutional framework and the location of registries; the transparency and openness of dialogue; information sharing; clearly articulated rules and regulations; and realistic monitoring and enforcement (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

The reduction of costs related to collaboration or the design and implementation of an institutional governance framework will be of concern to all parties involved, including development financiers (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Parties often find themselves embroiled in agreements that are beyond their financial and technical ability to implement (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

4. Institutional Architecture

Upon recognition of the institutional goals, the focus turns to the general framework of institutional governance. This section examines specific governance instruments which aim to ensure effective and efficient planning and management. Effectiveness of the governance regime is greatly influenced by the extent an institution's architectural design is aligned with institutional goals (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

4.1 Organizational efficiency in the aspect of cooperation

According to G. S. Hearns et al., (2014) “The subsidiarity principle (the principle that a matter ought to be handled by the smallest, lowest, or least centralized authority capable of addressing that matter effectively) is an important organizing principle of institutional design”. Furthermore, an important prerequisite for strong governing bodies is usually a clear mandate that defines cooperation among the various national and cross-border organizations involved in the institution (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

4.2 Information

The states and institutions of the basin must always have «access to reliable and trustworthy data and information about the status of resources and how they are affected by resource use and development, land-use practices, and climate change» in order to effectively manage a transboundary basin (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Creating agreements and networks to share data and information between states and institutions in a shared basin helps maximize securitization in coastal regions by fostering confidence and a common view of the resources (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Sharing of data and information is essential for data integration, collaborative modeling, and general monitoring protocols critical features of successful institutional mechanisms for uniform and flexible management of water resources (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

4.3 Rules and norms

Vote and participation. A good institutional structure should have strict rules that cover decision-making body membership rules, decision-making levels, and voting rules. Participation in the governance institutions must be well-defined (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Rules are usually designated by specific signatory representatives who can interpret and modify agency rules (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Regulations shall also specify how to vote, especially when unanimity, consensus, and favorable votes are necessary.

Dispute resolution. Disputes may arise from differences in the understanding of the terms of the treaty or failure to comply with the treaty itself (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Disputes can also occur due to changes in terms that modify the effectiveness of the treaty for several partners (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Thus, the inclusion of clear conflict resolution mechanisms is usually a necessary prerequisite for effective and long-term governance (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Disputes are handled through various mechanisms, such as negotiation, non-binding mediation, binding arbitration, and adjudication by an international institution (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Enforcement and monitoring. After the signing of an agreement, the successful implementation of the treaty is dependent on not just on final conditions of the treaty, it also depends on the capacity to enforce those conditions. The designation of supervisory authorities with decision-making and enforcement powers is a major step in preserving joint-governance institutions (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Feasibility. Each institution must have the corresponding capabilities to fulfill its mission. That includes financial and personal sources as well as political assets necessary to carry out policy and implement programs that may be depressing but important to pursue (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

The governmental support of all littoral basin states has to be secured and guaranteed to afford the institution the ability to articulate and effectively carry out its responsibilities (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014 ) . Furthermore, sufficient financing for effective institutional management helps build greater unity among the stakeholders and develop more effective resource management strategies, which will turns, to assist in securing funding for massive infrastructure or development cases (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Adaptability. According to the author's analysis, effective institutional governance frameworks commonly include some level of adaptability to accommodate public opinion, changing basin priorities, new information and monitoring technologies (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). Most basins do not have enough institutional agility and ability to cope with the expected impacts of climate change (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Openness. Involvement as a governance goal ranges from merely giving information to stakeholders not expecting participation to advise, accommodations, direction, collaboration, actually shared policymaking and reporting (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014). The level of involvement that seems to be required or preferred as a governance goal depends on a number of factors, ranging from whether and to what extent impacted actors are needed or preferred for resilience, to whether or to what extent the impacted actors can realistically be identified and pressured to do so (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014).

Finally, openness is a balance among the desire to be open and the ability to be open, i.e., financial opportunities. “The level of initial openness will likely influence what is prioritized at the institutional objectives stage, and thus what institutional architecture becomes.” (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014. 108).

Conclusion

In this theoretical review, we had familiarized ourselves with the concepts of several types of transboundary water management regimes in terms of both their theoretical and empirical aspects. The term «regime» was also used, which indicated a form of management that was stable through the implementation of a certain level of arrangements.

The result is that the regime is not the action itself, but the context of the action, the analysis of which makes it possible to portray different perceptions, priorities, and ways of using water. Concerning the theory of effective transboundary water resources governance, perhaps the above five steps of the approach can serve as a favorable outline for organizing institutional arrangements in the Central Asian water management situation.

Also considered the concept of institutional architecture and reflected that institutional architecture is no cure-all for everything that gets in the way of proper transboundary water management. Engineering continues to be more of an art than a science where mentioned some tentative observances and findings of what can contribute to good transboundary water management in terms of institutional architecture (G. S. Hearns et al., 2014. 108).

References:

1. C. Bréthaut and G. Pfieger. “Governance of a Transboundary River.” Palgrave Studies in Water Governance: Policy and Practice. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978–3-030–19554–0_2

2. Sehring, J. “Path dependencies and institutional bricolage in post‐Soviet water governance.”; Water Alternatives 2(1): 61‐81. 2009.

3. Barbar Janusz-Pwletta. “Current legal challenges to governance of transboundary water resources in central asia and joint management arrangements.”: BULLETIN Abay Kazakh National Pedadgogical University. 2014.

4. Glen S. Hearns, Taylor W. Henshaw, Richard K. Paisley. “Getting what you need: Designing institutional architecture for effective governance of international waters.” Environmental Development 11 (2014) 98–111. 2014. www.elsevier.com/locate/envdev